What is Brahm, Adhyātma, Karma?

अक्षरं ब्रह्म परमं स्वभावोऽध्यात्ममुच्यते।

भूतभावोद्भवकरो विसर्ग: कर्मसञ्ज्ञित:।।8.3।।

akṣharaṁ brahma paramaṁ svabhāvo ’dhyātmam uchyate

bhūta-bhāvodbhava-karo visargaḥ karma-sanjñitaḥ. (8.3)

The Blessed Lord said The immutable is the Supreme Brahman; self hood is said to the entity present in the individual plane. By action is meant the offerings which bring about the origin of the existence of things.

~ Chapter 8, Verse 3

✥ ✥ ✥

अधिभूतं क्षरो भाव: पुरुषश्चाधिदैवतम्।

अधियज्ञोऽहमेवात्र देहे देहभृतां वर।।8.4।।

adhibhūtaṁ kṣharo bhāvaḥ puruṣhaśh chādhidaivatam

adhiyajño ’ham evātra dehe deha-bhṛitāṁ vara. (8.4)

That which exists in the physical plane is the mutable entity, and what exists in the divine plane is the Person. O best among the embodied beings, I Myself am the entity that exists in the sacrifice in this body.

~ Chapter 8, Verse 4

✥ ✥ ✥

Questioner (Q): When Arjuna asks, “What is Brahm, adhyātma, karma, adhibhūt, adhidaiva, adhiyagya?” Shri Krishna’s response is presented in the verses above. I want to understand the meaning of adhyātma, karma, adhibhūt, adhidaiva, adhiyagya and why do they prefix ‘adhi’ here?

Acharya Prashant (AP): So, to complete these two we must also go to the two verses that precede these. I will read them out for you. These are the opening verses of the 8th chapter:

अर्जुन उवाच।

किं तद्ब्रह्म किमध्यात्मं किं कर्म पुरुषोत्तम।

अधिभूतं च किं प्रोक्तमधिदैवं किमुच्यते।।8.1।।

अधियज्ञ: कथं कोऽत्र देहेऽस्मिन्मधुसूदन।

प्रयाणकाले च कथं ज्ञेयोऽसि नियतात्मभि:।।8.2।।

arjuna uvācha

kiṁ tad brahma kim adhyātmaṁ kiṁ karma puruṣhottama

adhibhūtaṁ cha kiṁ proktam adhidaivaṁ kim uchyate. (8.1)

adhiyajñaḥ kathaṁ ko ’tra dehe ’smin madhusūdana

prayāṇa-kāle cha kathaṁ jñeyo ’si niyatātmabhiḥ. (8.2)

Arjuna said, Krishna! What is that Brahman? What is Adhyātma? and what is Karma?, and what is Adhibhūt and what is Adhidaiva? Who is Adhiyagya? and how does he dwell in the body? And how are you to be realised at the time of death by those of steadfast mind.

~ Chapter 8, Verses 1-2

✥ ✥ ✥

Then comes the reply of Shri Krishna in the next two verses.

“Shri Bhagavan said, The supreme indestructible is Brahm, the supreme indestructible is Brahm. One's own self”—by ‘self’ here is meant the individual self, not the Supreme Self—”one's own self is called adhyātma, and the primal resolve of God Visarga which brings forth the existence of things is called Karma.”

What is Brahm? Brahm cannot be known by affirmation of positive instruction. All that we know of has characteristics, and we know a thing by its characteristics, its properties. That is the defining thing about a thing, it’s characteristic. Remove the characteristics, and it will be very difficult to talk about the thing at all. Is there a thing without its characteristic? No. So, that's the world we inhabit. A world of properties, a world that can be named, pointed at, described as a story, pictured, projected. That's what this world is, right?

Unfortunately for us, this world does not take our inner wellbeing too far. We exist in the world, alright, but we never quite find absolute peace in the world—and the world means the one that has characteristics, the one that comes and goes, the one that is within the scope of time. Is there a world without things? And everything arises at a certain point and disappears at another point. So, there comes a point of time when things with all its names, properties, etc. suddenly come into being—not even suddenly; there is a cause-effect chain, so there always are causes behind everything even if the thing seems to appear at once, abruptly—and then there comes another point in time when the thing disappears.

Brahm is for the ones who no more assign value to these things, because they are experienced enough, probably intelligent enough to have tested these things, penetrated these things, and discovered that they can only do so much good and nothing beyond that.

Things are useful in our day to day business. We require things, right? We require clothes. The body is there, the body is in itself a thing. How can we say things are all useless? Correct? We need food, we need water—all things. Even thoughts are subtle things. So, things have their utility. Maybe things have great utility; maybe things take you as far as the 99th milestone, but if 100 is the destination, things somehow fail in reaching there.

That is when adhyātma kicks in. That is when you realize that you need to have something beyond things. For things, the world cannot be totally relied upon, and somehow the mind seeks perfect security; the mind doesn’t come to rest unless and until it is assured of total security. Therefore we need Brahm, something that is indestructible.

What is Brahm? A reality? No, Brahm is not real. From where I look at Brahm, Brahm is our utmost need. Brahm is our utmost need. Now call Brahm unreal at your own peril. All our life, all we deal with and encounter is destructibles, and all destructibles betray us at some point or the other, don't they? That's their name, that's their nature; to come and go, to arrive and to perish. Now, at our own risk, can we deny something that never destructs? For if there is nothing that never destructs, then we are condemning ourselves to a hellish life, aren’t we?

We live in constant restlessness because nothing lasts; therefore, we require something that lasts. Brahm is that. Therefore, Brahm cannot be something within the universe because there is nothing in the universe that lasts.

Therefore, Brahm has to be beyond; therefore, the word ‘transcendental’.

Now, you could say, argue that Brahm could as well be a childish fantasy. We want something and we are not able to find it in this world, so maybe we are just fantasizing that thing. We are saying, we want perfect security, we want something reliable, indestructible; therefore, we are just conjuring the concept of Brahm. The argument has substance, but then, the argument is defeated by the accomplishment of those who were able to achieve rest. That's the final proof.

If Brahm is a mere concept, a childish fantasy, then the peace associated with Brahm too would be merely an illusion. But what if there are people who did attain to that peace? If even one person managed that, it proves that the stuff is doable.

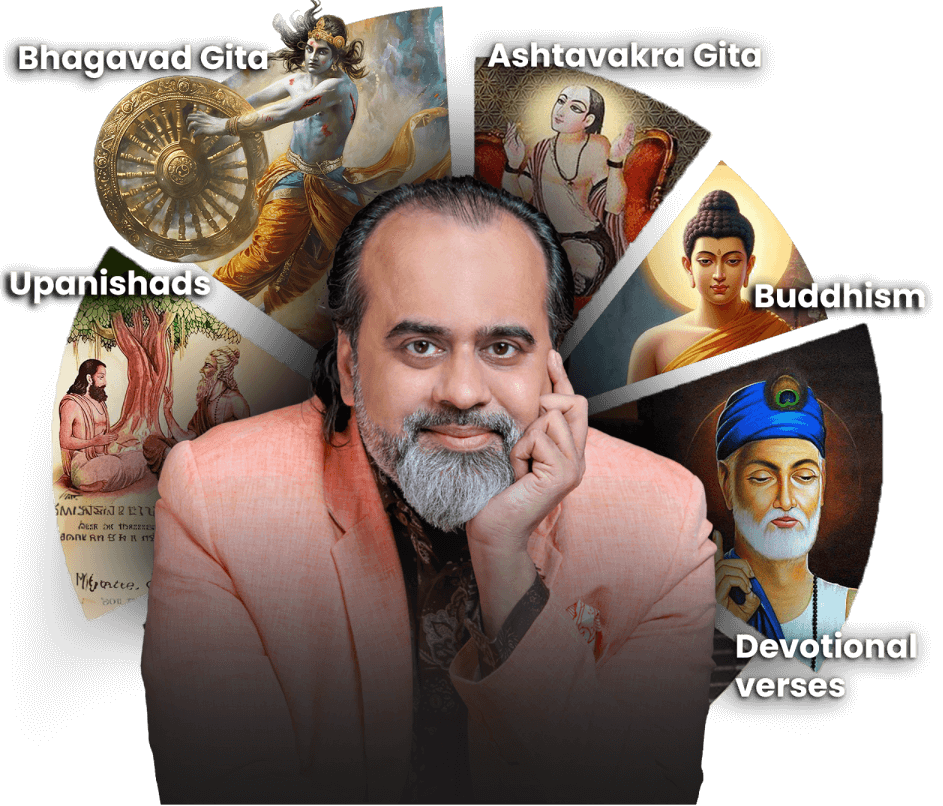

Alright, but is there proof that even one person reached there? Well, the proof here lies in the comprehension of the one who seeks the proof. You have the words of Krishna, you have the life of Jesus, you have the songs of the thousands of fakirs and saints, you have the revelations that came to Mohammed. If you want to assert that all of this is self-delusion, then alright. But if you go through what those people have said and are left awestruck even by a single verse, then it means that the beyondness is indeed possible. And if beyondness is possible, then you better not dismiss Brahm.

To dismiss Brahm is to dismiss the possibility of your own peace. There is no other proof.

When you are going through the scriptures, there comes a point where you ask yourself, “But this can’t occur to a normal mind. How did this person dream this up? It is simply not possible that this kind of stuff can occur to the sharpest kind of mortal intelligence—then where did these lines come from? Did some aliens come and teach these things?”

But then, what kind of supremacy and specialty do you want to associate with aliens? At most a higher IQ. What if you clearly see that the words in front of you are not a function of IQ at all? Instead, those words are coming from extremely metaphysical insight. It is so incisive, it is so rare that one clearly hesitates in calling it a usual worldly phenomenon. It is something else. It just can’t occur to a normal man or woman. That's the only proof. Otherwise, everything is destructible, everything is ephemeral. And if everything is ephemeral, then we are condemned to live as mental patients; people with mind-related disorders.

Then, ‘adhyātma’. Going into one’s own mind is adhyātma; enquiring into the nature of one’s self. Remember, one’s self, not the Self. And one’s self means the personal self, the mind. You are not enquiring into Ātmān or Brahm; no enquiry is possible into Ātmān or Brahm. Brahm or Ātmān are the endpoint of all enquiries. All enquiry stops at them; you don’t enquire into them. Having enquired for long, when you come to the peaceful end of your enquiry, that is Brahm or Ātmān.

Therefore, *adhyātma is not at all about enquiring into Ātmān. Adhyātma is an honest exploration into the facts of one's own daily life. How do I live, how do I think, how do I relate, how do I eat, how do I earn—that's adhyātma. Adhyātma, therefore, is no mumbo jumbo. Adhyātma is not about some esoteric practices or cult-based rituals or verses in archaean languages. Adhyātma is a simple curiosity that makes you ask, ‘Hell, what did I just do?” Is that too much? *

You are roaming around, let's say in a shopping mall, and thoughts are roaming around in your head, and suddenly you pause and say, “Wait! What’s going on?” That's adhyātma. Therefore, adhyātma has to be real-time; it has to be like the light that shines on your daily usual activities. Therefore, it cannot be something special, it cannot be something divorced, separated or bifurcated from the rest of your life. There is nothing greatly complicated about the phrase ‘know thyself’. ‘Know thyself’ is adhyātma, and ‘know thyself’ does not mean that you have to earn a doctorate in the complicated business of self-knowledge. Who are you? The one that you right now are. The one who is listening attentively; the one who is scratching his back; the one who intermittently feels interested in the neighbour rather than the lecturer. That's the one we are. Figuring this out and acknowledging it is adhyātma.

What does adhyātma have to do with Brahm? In the realm of adhyātma, we keep hearing of Brahm frequently, don’t we? We just talked of Brahm, and now we talked of adhyātma. How are the two related? Brahm, we said, is the endpoint of all enquiry, and adhyātma is the enquiry itself. Do you see this? If you are really adhyātmic, Brahm is what you will get. I am using the word loosely; you don’t really get Brahm, but just to make the point clear. Brahm is the endpoint of all the enquiries. Poetically said, that is the endpoint at which even the enquirer vanishes because the enquiry is resolved. Now, what will the enquirer do? When the disease is cured, does the patient exist at all? If the disease is gone, would you still be called a patient? So you are gone, right? That’s Brahm, you are gone. The process that makes you go away is called adhyātma.

Then, ‘karma’. By ‘karma’ is meant the offerings that bring about the existence of things. The world does not just exist; it exists to somebody. Therefore, when Arjuna asks, “What is karma?” Shri Krishna will not give him a merely theoretical reply. What he is telling Arjuna is, what is the right karma for you, or rather, what is the very definition of right karma. Except for that, all other action is bad action.

When somebody asks you, “What is action?” and if you are a well-wisher to that person, you would want to tell him the highest possible definition of action, right? That's what Shri Krishna is doing here. Shri Krishna is saying that what you do to come to the right state of the universe is karma. Sacrificing that which is not needed by you, sacrificing that which keeps you in illusion, that alone is karma. All else can be called as vikarma or distorted karma.

We all act, right? All our life we have to compulsorily act. Shri Krishna is telling Arjuna how to act. Act in the manner of sacrifice—that's the gold standard. Act in the manner of giving up, not in the manner of taking in, absorbing or accumulating. Every action of yours has to be the action that reduces you. That which makes you give up some part of the inessential stuff we carry, that alone is Karma.

But that's not the kind of action that we find ourselves or others engaging in usually. Then those actions do not deserve to be called as karma either. When Shri Krishna says ‘karma’, by default it means ‘nishkam karma’. Remember who is using the word; the word is colored by the one who is uttering it. So, act in a way that reduces you.

Now, tell me how adhyātma and karma are related? Adhyātma is an inquiry into your form, your shape, your composition, your structure, and karma is the positive intent, the change that you bring about to give up all that is seen as useless in the process of self-inquiry. You looked into yourself and you found a lot of stuff that was needlessly present. Then the right action is to get rid of those things, and it is not quite easy; it may take some effort, some doing to tear those things away from your inner personality. Those things have been with you since long; it is not easy to drop them. They have to be torn apart. That is action.

Just as action for Arjuna on the battlefield is fighting with his relatives—not easy at all. Shri Krishna tells Arjuna, ”Clearly it is not about killing somebody outside of you; you have to fight your own inner weakness. As far as those people are concerned who you see in front of you, they are already dead, they are gone. So, it is not about killing Duryodhana or Duhshasana; it is about fighting your own attachment that is making you subvert Dharma itself. You very well know, Arjuna, that the right thing to do at this moment is to put the right man on the throne of Hastinapur. You very well know who that right man is. You very well know whether Yudhisthir is a worse candidate compared to Duryodhana. You know which of these two should occupy the throne, and you also know the repercussions of the wrong man occupying the throne. We are talking of monarchy, not democracy. In a monarchy, the personality of the monarch decides the fate of an entire population. You know, Arjuna, who should be the monarch, but see, your inner entanglement is not allowing you to fight. Therefore, karma for you is to fight.”

Do you see what karma means? Something that helps you get rid of your inner weaknesses. Whenever you are acting—and you always are—keep asking yourself, ”That which I am doing right now, is it liberating me of my weaknesses or is it consolidating, even decorating my weaknesses?”

Then—it is a long question in itself; it contains the gist of the entire session—then the question moves over to the next verse and asks about the meaning of adhibhūt.

What is ‘adhibhūt’? ‘Bhūt’ refers to the primal element; ’bhūt’ refers to the primal elements. In classical literature when we refer to ‘bhūt’, it means the fundamental, primal elements.

What is adhibhūt then? All that you see around yourself is adhibhūt. And all that, therefore, which relates to this world or arises from this world is called adhibhūtic. This is adhibhūt and anything that arises from it is adhibhūtic.

Then, ‘adhidaiva’. What is adhidaiva? Shri Krishna says, the shining Purusha is adhidaiva. In the translation, it is mentioned that the shining Purusha, the adhidaiva is Brahm. I beg to differ with the translation. No, adhidaiva doesn’t refer to Brahm; adhidaiva refers to Īśvara. There is a great difference between these two. For example, when troubles come to you, scriptures will want to differentiate between adhibhūtic and adhidaivic troubles. That does not mean that the adhidaivic trouble has been sent upon you by Brahm. If adhidaiva is Brahm, then adhidaivic stuff is being operated upon by Brahm. But Brahm is a non-operator, non-doer. Brahm doesn’t do anything. Adhidaiva is not Brahm; adhidaiva is consciousness itself. So, by adhibhūt you refer to all that which is unconscious, and by adhidaiva you refer to consciousness itself, the one that watches everything that is unconscious. Jaḍa and chaitanya—jaḍa is adhibhūt, and chaitanya is adhidaiva.

Then, what is ‘adhiyagya’? Adhiyagya now refers to Brahm, the one to whom you offer all your sacrifices, the one immeasurable ocean into which all currents of your offerings and all your actions vanish. That is adhiyagya, that is Brahm. Krishna does not mention Brahm here; instead he says, ”I am adhiyagya.” But then, who else is the Krishna of Bhagavad Gita except Brahm? When Krishna says, “I am adhiyagya,” verily he means Brahm.

So, there is adhibhūt that you could think of as the Aparā Prakriti of the previous chapter; there is adhidaiva that you could take as Parā Prakriti of chapter 7; then there is adhiyagya that you could take as the Supreme Truth, Ātmān, or Brahm of chapter 7. The same model holds good here as well, though explained or referred to in a different way.

Are all these terms clear?